“[T]he prairies or grassy plains begin to be prevalent, and the trees to decrease in number and magnitude.” (:155) Nuttall made this entry in his journal on April 23, 1819 as he neared Fort Smith from the east, working his way upstream. Later, as he continued west, he made similar comments twice more:

–On July 7, about 10 miles upstream from Fort Smith, he wrote: “The depression of the forest also begins to be obvious.” (:185)

–On July 11, a few miles further upstream, having just passed what are today called Webber’s Falls, he elaborated: “The variety of trees which commonly form the North American forest, here begin to very sensibly diminish…From hence the forest begins to disappear before the pervading plain. (:189)

On June 29, 2019 a field workshop will explore Fort Smith area prairies, with Nuttall as our guide. We will visit Massard, Cedar, and Long Prairies–each described by Nuttall–and will also, going east rather than west, visit prairie preserves of the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission in the Charleston area.

Register to go with us at https://www.eventbrite.com/e/once-and-future-prairies-of-fort-smith-and-the-arkansas-river-valley-tickets-62811235095

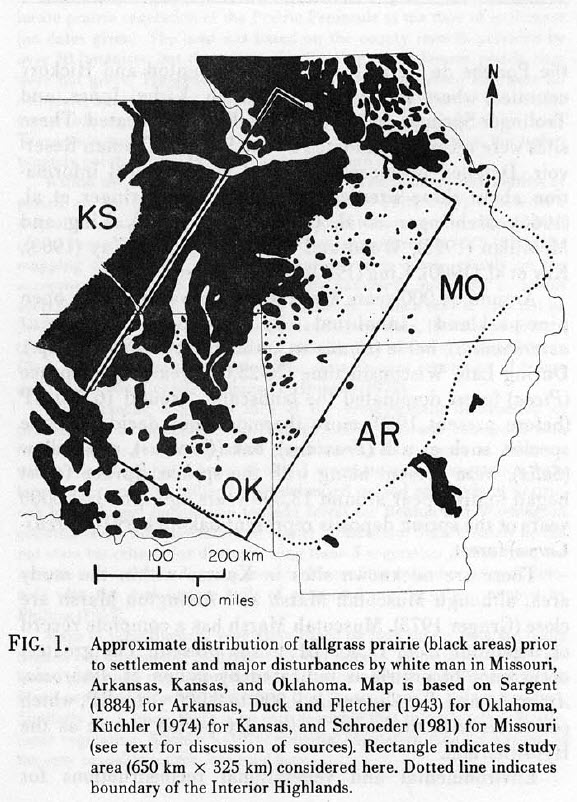

By a coincidence of history, geology, and ecology, the Arkansas-Oklahoma stateline, on which Fort Smith lies, is a good first-order approximation of a major North American ecological transition zone. If you are traveling west, it is the end of, the western extent of, the oak-hickory forests that dominate the eastern half of the US, and the beginning of, the eastern extent of, the prairies that extend west to the foot of the Rocky Mountains. Though not generally locally recognized as such, the prairies that Nuttall saw and described around Fort Smith, and southwest from there through the Poteau River valley, are true tallgrass prairies. All the “big four” grasses–big bluestem, little bluestem, Indiangrass, switchgrass–grow here. Unlike further west, the prairies don’t extend for hundreds of miles. Here they intertwine with wooded areas on hills and ridges, and along streams.

In the early 1980s Nancy Eyster-Smith at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville explored the ecotonal nature of these prairies in her Master’s thesis. She summarized her study in a paper published in Proceedings of the Eighth North American Prairie Conference (1982).The map below is from her report (Eyster-Smith 1982. The prairie-forest ecotone of the western Interior Highlands: an introduction to the tallgrass prairies.)Eyster-Smith’s map is a pretty good approximation for the locations and extent of the western Arkansas River valley prairies, but just across the state line into Oklahoma, the map significantly underestimates the extent of prairie.

One disadvantage we have for the Oklahoma portion of the map is that because eastern Oklahoma became the Choctaw and Cherokee Nations, no US General Land Office mapping was undertaken there for decades after it was completed in Arkansas. GLO maps for western Arkansas were made in the 1830s and 40s, while the first mappings of eastern Oklahoma were not completed until the late 1890s, after more than 60 years of Choctaw and Cherokee settlement.

Eyster-Smith’s map also doesn’t convey the importance of prairie grasses and forbs (wildflowers) as understory in the wooded lands of western Arkansas and eastern Oklahoma, the Ozarks and the Ouachitas, though that was not the focus of her study. I like her map as a good start, from which we can begin to begin to understand this area as a major historical and ecological transition zone.