Bokoshe, OK prairie- native hay meadow- looking south to Cavanal Hill (Photo by Amy Buthod, OU).

On April 23, 1819, Nuttall was working his way west (upstream) on the Arkansas River. As he neared Fort Smith, he wrote:

“[T]he prairies or grassy plains begin to be prevalent, and the trees to decrease in number and magnitude.” (:155)

At the invitation of Major Bradford, he spent the next two months using the garrison (the first Fort Smith) as his base for botanizing the area, including a trip south through the Ouachitas down to the Red River.

On July 6, he again proceeded west, upriver to Three Forks (the confluence of the Verdigris and Grand rivers with the Arkansas).

The next day, July 7, only about 10 miles upstream from Fort Smith, he wrote:

“The depression of the forest also begins to be obvious.” (:185)

By a coincidence of history, geology, and ecology, the Arkansas-Oklahoma stateline, on which Fort Smith lies, is a good first-order approximation of a major ecological ecotone. If you are traveling west, it is the end of, the western extent of, the oak-hickory forests that dominate the eastern half of the US, and the beginning of, the eastern extent of, the prairies that extend west to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains.

Though not generally recognized as such locally, the prairies that Nuttall saw and described around Fort Smith, and southwest from there through the Poteau River valley, are true tallgrass prairies. All the “big four” grasses–big bluestem, little bluestem, Indiangrass, switchgrass–grow here. Unlike further west, these prairies don’t extend for hundreds of miles. Here they are a few miles in extent and intertwine with wooded areas on hills and ridges and streams.

Nuttall’s description of Massard Prairie begins (without naming it):

“On the 29th [of April], I took an agreeable walk into the adjoining prairie, which is about two miles wide and seven long. I found it equally undulated with the surrounding woodland, and could perceive no reason for the absence of trees, except the annual conflagration.”

Today we understand that a combination of shallow soils and fire interact to maintain this prairie.

As one goes further west into Oklahoma the small prairies grow larger and the trees decrease, as Nuttall describes. From the foot of Sugarloaf Mountain to the foot of Cavanal Hill, from the town of Spiro to the community of Monroe, is approximately a 10 mile by 20 mile area, virtually all of which was once prairie. Significant remnants of prairie persist, maintained today by annual mowing for hay.

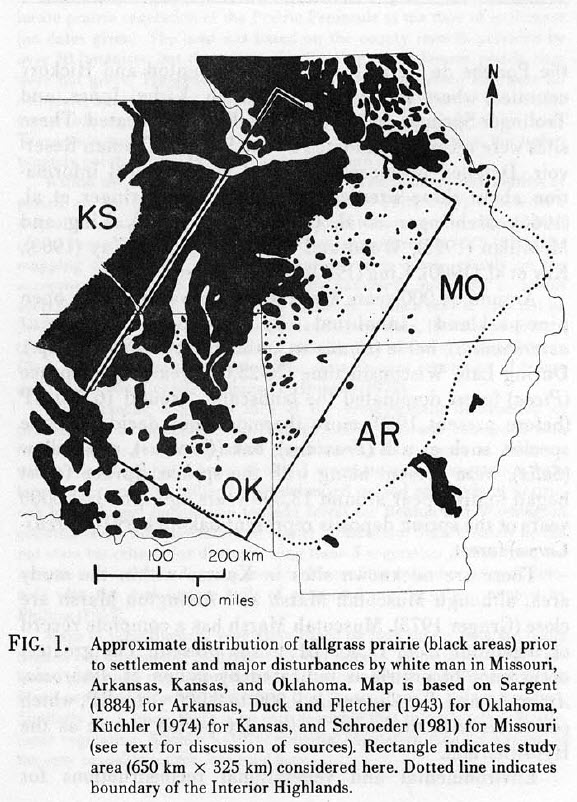

In the early 1980s Nancy Eyster-Smith at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville explored the ecotonal nature of these prairies in her Master’s thesis. She summarized her study in a paper published in Proceedings of the Eighth North American Prairie Conference (1982).

Here’s a map she produced for that report:

an introduction to the tallgrass prairies.

Eyster-Smith’s map is a pretty good approximation for the distribution of the western Arkansas River valley prairies, but just across the line into Oklahoma, the mapping significantly underestimates the extent of prairie.

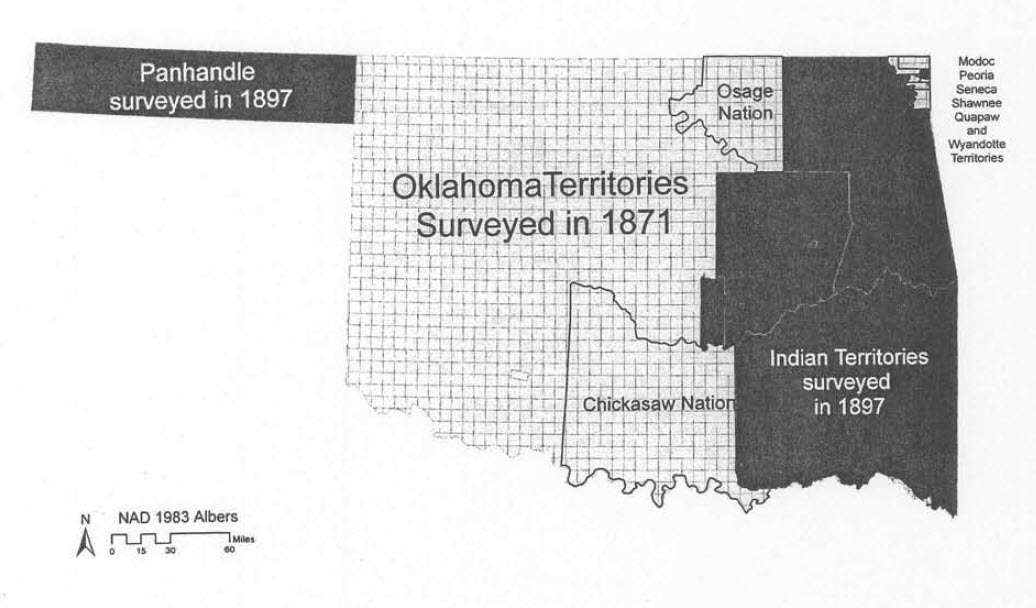

One disadvantage we have for the Oklahoma portion of the map is that because eastern Oklahoma became the Choctaw and Cherokee Nations, no US General Land Office mapping was undertaken here for several decades. GLO maps for western Arkansas were made in the 1830s and 40s, while the first mappings of eastern Oklahoma were not completed until the late 1890s, after more than 60 years of Choctaw and Cherokee settlement.

Eyster-Smith’s map also doesn’t convey the importance of prairie grasses and forbs (wildflowers) as understory in the wooded lands of western Arkansas and eastern Oklahoma, the Ozarks and the Ouachitas, though that was not the focus of her study.

I like her map though as a good start, from which we can begin to begin to understand these lands as a major historical and ecological transition zone.

How may a changing climate affect this transition zone in years to come? There seems to be both a warming, which might favor prairie, and an increase in rainfall, at least in some years, which would tend to favor trees.

Explore these questions with us on one of this year’s Nuttall bicentennial excursions!

- On April 27, 2019, beginning where Nuttall did, at Belle Point in Arkansas, we will explore Massard Prairie and proceed south and west to the Poteau area prairies. Go to: https://ktcbis.augusoft.net, select Poteau Campus, and then Personal Enrichment to reach the course description and enroll.

- On May 17-18, 2019, we will begin at the confluence of the Poteau with the Arkansas and end near the confluence of the Kiamichi with the Red. We will explore both the Poteau River valley and the Kiamichi River valley through Nuttall’s eyes. Go to: https://ktcbis.augusoft.net, select Poteau Campus, and then Personal Enrichment to reach the course description and enroll.

- On June 29, 2019 we will concentrate on the Fort Smith area prairies–Massard, Cedar, and Long–described by Nuttall, and will go east rather than west, to visit prairie preserves of the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission in the Charleston area. Registration info coming soon at BXDWorkshops.com